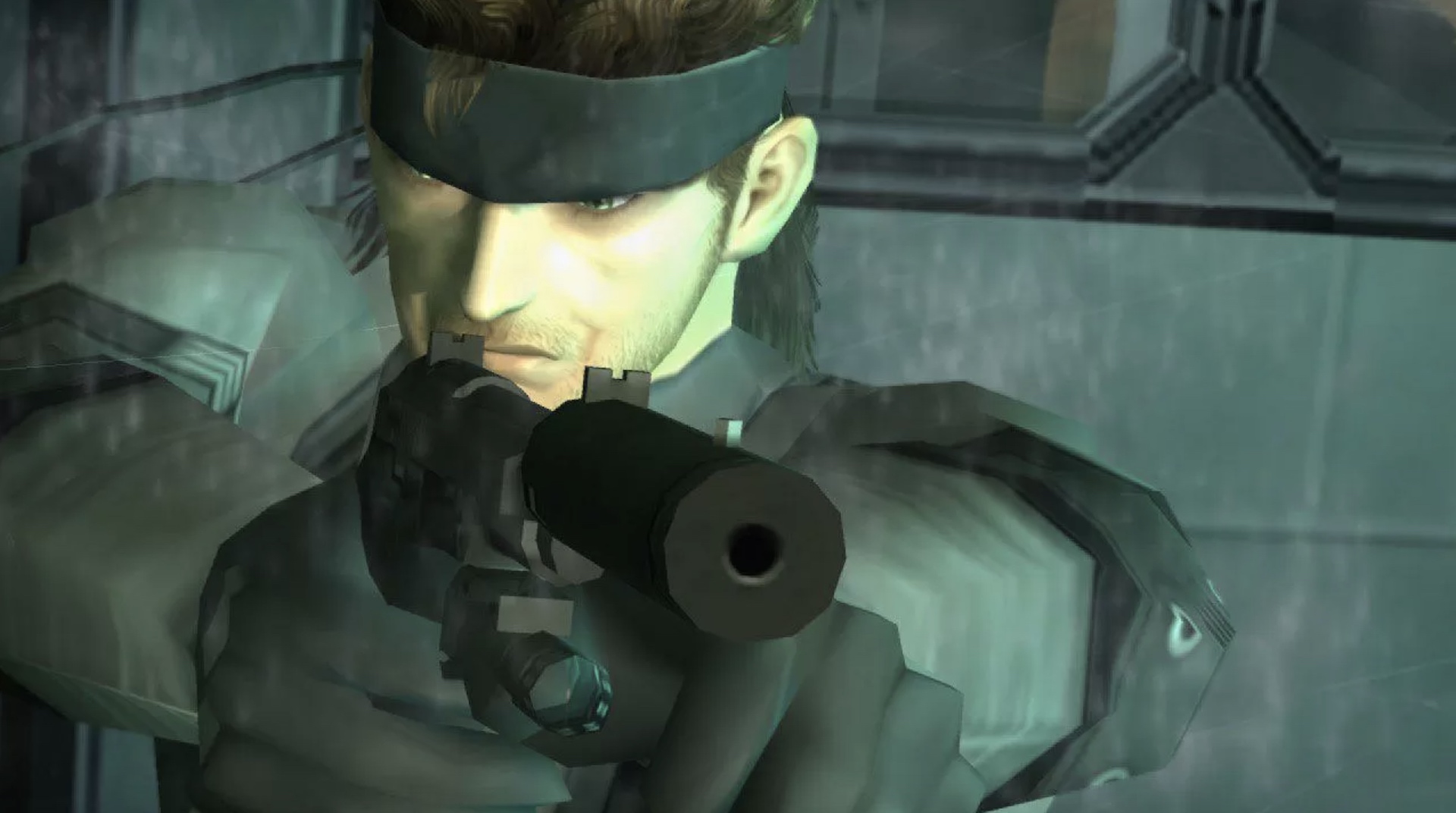

As attested by Metal Gear Solid creator Hideo Kojima himself, 2001’s Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty was primarily intended to be a wake-up call to the fledging digitisation occurring in contemporary global society. Its story is heralded as Kojima-san’s most prescient work to date, with hyper-focus on mass information via digital communication channels, a zeroing in on the burgeoning proliferation of and dependence on computer technology, on the internet and its torrent of information, and the way in which these systems exposed the masses to misdirection. MGS2’s allusions to fake news were nebulous concepts at the turn of the century but nowadays some twenty-two years later are now etched into mainstream public consciousness.

Set four years after Sons of Liberty in the Metal Gear Solid timeline, Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots is – in Kojima’s words – centred on the digitisation of the battlefield. Drones, personification of weaponry, weapon laundering, and soldiers who’ve surrendered their freewill and emotions to nanotechnology are the vehicles in which this digitisation is explored. Instead of exhibiting complex human emotions and powers of reasoning, MGS4’s private militia are now pawns of a proxy war rendered cold and clinical. They’re killing machines expunged of emotion, soulless but adept, instead sharing thoughts and feelings across a vast network known as the Sons of the Patriots – the SOP – to enhance battlefield performance throughout their entire military unit. This SOP system is governed by artificial intelligence, removing any shred of human interference.

From these brief synopses, we can see both these Metal Gear entries explore complex themes of control. MSG2 poses a reality whereby radical and opposing ideas can be erased through mass dis-information distributed by those in power to maintain mass control. MGS4 opts to showcase the dehumanisation of individuals, of soldiers who’ve eradicated their identities to dispassionately fit into a machine of war; a continuous civil war waged via proxy by private military companies to prop up a world economy skewed to their own agenda. With Metal Gear Solid 4 marking its fifteenth anniversary since release this year, now’s as good a time as any to analyse if its themes have proved as prescient as Metal Gear Solid 2’s were.

Well, straight off the bat, autonomous warfare is a thing now. Drones are utilised as machines of war, controlled by humans yes but with the danger of placing people over enemy lines removed. Artificial intelligence has seen major developments in recent years, with systems capable of writing entire theses in the palm of everyone’s hand. AI originators and a barrage of commentators are extolling the existential threat posed by AI, and we’re not far off artificial intelligence being deemed a threat to humanity’s existence like a comet hurtling towards Earth. Speculative, and perhaps sensationalist sure, but AI anxiety amongst workers afraid of losing their jobs is an established worry across the globe.

The soldiers of Metal Gear Solid 4 are entrenched so deeply into a system which suppresses their natural emotions that their removal brings negative feelings flooding back like a tidal wave – fear, stress, guilt, regret, trauma; these are complex emotions expected that soldiers will experience. Their long-term suppression then sudden reintroduction leads to total shellshock, a complete overwhelming of the individual. As a result, a connection to the SOP system becomes their dependency like a addiction.

There’s a school of thought out there that this particular element of MGS4’s themes are a mirroring of Hideo Kojima’s experience and perception of the video game industry. The rationale behind this is in Snake’s stoic allegiance to his core values, of code, loyalty, honour, and a reason to fight. The will to keep going against insurmountable odds, decisions made through bravery in contrast to the remote-controlled militia-for-hire who’re fighting for whichever allegiance is programmed into their brains. Snake’s premature aging is as on-the-nose a signifier as anything too, acting as a visual representation of his status as aging relic against a freshly digitised world. As a reflection of video games at the time, well, it’s no secret game store shelves are stuffed with mindless, paint-by-numbers FPS titles. Kojima – as a creative auteur – would understandably feel the industry is evolving into creative bankruptcy as a result.

There’s also an argument that MGS4’s mind-controlled militia are a reflection on us as consumers in a capitalist society. The eradication of their humanity results in uniformity, or rather, a controlled conformity. You only need to scroll through social media to see regular people touting the same materialistic sentiment, showing off their expensive possessions – nice cars, glossy kitchens, multiple vacations abroad a year – painting a picture of their life far removed from the reality. Shedding the bad to portray something unrealistically good. It’s a desire to conform, plain and simple.

Metal Gear Solid 2 played a nifty trick on its players to illustrate the concept of misinformation. As is well documented by this point, following the game’s outstanding opening foray as Snake skulking through a hijacked oil tanker, the narrative unexpectedly shifts into the lens of combat newcomer Raiden. Many a player saw this as pure deception, as nothing in the game’s marketing alluded to such an extreme bait and switch.

The point though – as controversial as it is – was to put us the player into the shoes of a rookie on the battlefield. Raiden, at the point we assume command of him, has received all his combat experience via virtual reality training. As preparation for the real thing, VR will be sorely lacking. As the plot twists and turns, its revealed that Raiden is a test subject for the Patriots’ S3 Plan, a program initially believed to have stood for the Solid Snake Simulation via yet more misinformation but was actually a plan to manipulate world events via an agent, which in this case was Raiden. MGS2’s primary antagonist Solidus Snake is a third perfect clone of Big Boss alongside Solid Snake and Liquid Snake, with the three of them being sterile so as not to be able to reproduce.

The point here is to disprove the notion that behavioural traits can only be passed on genetically, for cultural artifacts and positive human emotions such as compassion, joy, and artistry can be passed on through cultural expression. Humanity, art, people – MGS2 argues – is influenced by forbearers, and no amount of misinformation or mind control can stop it. Kojima himself believes everything is a replication of something else, of inspiration from various sources, and to demonstrate this in-game we essentially play as Raiden through a recreation of Metal Gear Solid’s incident, a repetition of its bosses, cyborgs, Metal Gear encounters, with near-identical tertiary characters met along the way, and so on. Players at the time perceived this re-treading as a means of criticism but as a narrative arc it perfectly ties into the Patriots’ goal of mass-indoctrination of their own ideals. This was not a simulation to test the possibility of equipping every solider with the skillset of Solid Snake, but a road test for controlling civilians, and later on, the mind-numbed militia in Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots.

Both games receive acclimation for their portrayal of complex themes relating to politics, technology, and information against the backdrop of war. To choose one as better than the other is a futile exercise as both provide tangible gameplay evidence to perfectly exemplify their themes. MGS2 is perhaps more ahead of its time than MGS4, but whether that makes its themes better is a matter of opinion.

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, GamingBolt as an organization.