An often-overlooked fact is that both the Xbox 360 and Playstation 3 are capable of outputting a native 1080p image—and that’s in actual games, not video playback. Nearly a decade ago, back in the good old days circa 2009, Ascaron, a rather obscure German developer that later went bottoms-up, released Sacred 2. As you might’ve guessed from the name, Sacred 2 was a generic, questlog-filling time sink, a meh RPG if there ever was one. Except for the one thing that set it apart: At a time when Full HD wasn’t even where 4K is today, with the dearth of real content made up for by—gasp—upscaling DVD players and other varieties of snake oil, Sacred 2 offered a native 1080p experience on PS3 and Xbox 360, with a supersampling option thrown in for the players still hooked up to standard-def TVs. Of course, the only reason Sacred 2 ran at 1080p is because of visuals that hark back to vanilla World of Wacraft. You can do graphics, or you can hit a resolution target. But you can’t do both.

"Just like the PS3 and Xbox 360 were able to handle 1080p in Sacred 2—within the constraints of PS2-era tech—the PS4 Pro and Xbox One X are able to run existing games at 4K. Unfortunately, this means that today’s 4K don’t gain much apart from the (genuine) boost in crispness."

Does that remind you of something? In many ways, the PS4 Pro and the Xbox One X are this era’s Sacred 2-playing machines. 4K TVs are here to stay. But even today—between compressed Netflix streams that eat up your bandwidth and look worse than Blu-ray, and a set of “real” 4K movies that’s small enough to fit in a listicle—there still isn’t much native 4K content available apart from those demo videos they keep on loop at Best Buy. Of course, that’s going to change. Sometime in the early 2020s, 4K will be just as ubiquitous as 1080p is today and we’ll all be gaping at those 8K HDR monitors that are just around the corner. But until then, TV manufacturers—and by extension console makers—have a bit of a content problem on their hands. The solution? “4K” gaming. Simply running existing games at higher resolutions will give the owners of 4K TVs something to gawp at and which, of course, looks better than any existing Full HD content on hand. This is literally the only reason the PS4 Pro and Xbox One X exist.

But cynicism aside, these new consoles—the Xbox One X in particular—do give us a hint as to how image quality will shape up in the upcoming ninth-gen: the fabled Playstation 5 and Xbox One…X2? Xbox Two X? No, seriously, Microsoft, get your marketing act together.

Just like the PS3 and Xbox 360 were able to handle 1080p in Sacred 2—within the constraints of PS2-era tech—the PS4 Pro and Xbox One X are able to run existing games at 4K. Unfortunately, this means that today’s 4K don’t gain much apart from the (genuine) boost in crispness. Core technology is still limited within the bounds of what can run on 2012-era midrange hardware. Moreover, the mid-gen refreshes consoles—the PS4 Pro in particular—aren’t that much more powerful than their predecessors. Just running existing 1080p titles at 4K requires a 4x increase in rendering power—there simply isn’t enough headroom to deliver much more than that. Moreover, the One X and the PS4 Pro have scarcely improved their CPU power relative to the Xbox One and PS4—and those two weren’t that great a step up from the PS3 and Xbox 360 either in that respect.

"While 2015’s The Witcher 3 certainly offered sweeping landscapes and an engrossing narrative, the open world structure did expose some of its technical limitations: the way Geralt interacts with the world and with items hasn’t changed much since the The Witcher 2."

Substantially increased processing power is the only way (apart from GPU compute, which, for obvious reasons, saps away rendering power) to bring about a paradigmatic shift in games—leveraging more advanced AI, physics, and world-building to create new kinds of gameplay experiences, rather than making existing gameplay prettier. 2014’s Assassin’s Creed: Unity, which chokes on consoles due to CPU bottlenecking, but absolutely shines on high-end PC remains one of the few examples of what such a paradigm shift would look like.

When the (real) next-gen arrives, CPU and GPU hardware will reach the stage where 4K/30 FPS and 4K/60 FPS titles will both look better and offer greater immersion than anything that currently exists on the market. But what would this actually look and feel like?

While 2015’s The Witcher 3 certainly offered sweeping landscapes and an engrossing narrative, the open world structure did expose some of its technical limitations: the way Geralt interacts with the world and with items hasn’t changed much since the The Witcher 2. The majority of in-game assets are essentially “props,” static, place-settings—cages, tables, and shelves—that contribute to atmosphere, but don’t really exist in a tangible manner. In that sense, interactiveness is paper-thin when it comes to much of the game.

Of course, it can be argued that shuffling pots and pans around isn’t the purpose in a narrative title, but that’s exactly the point: in the coming generation, greater computing resources will remove the constraints that result in staged environments, instead creating lived-in, interactive spaces, irrespective of genre. Increased interactibility can also result in emergent, player-driven experiences that blur genres even more.

"But in today’s games, fence-posts don’t exist objectively. They either serve to funnel you into a fixed location or act as “destructible” objects that fade away the moment you turn the camera away (or even before)."

Take fence-posts for example. In today’s Far Cry games fence-posts are interactive, if you limit your definition of interactibility to destroying them with your car. This has some rather disconcerting post-structuralist implications. In the real world, at least you can objectively separate the existence of a fence-post from discourses about a fence-post—what it could be, and how it could be used. In the real world, you could dig up a fence-post, carve it into a sculpture, or write about it. In the real world, fence-posts have inherent properties—they’re made of wood, they have a certain weight—that don’t depend on your specific actions. That means you can use them in any conceivable way—or ignore them entirely.

But in today’s games, fence-posts don’t exist objectively. They either serve to funnel you into a fixed location or act as “destructible” objects that fade away the moment you turn the camera away (or even before). If the appalling compute limitations of the current consoles go away, and if in-game items become defined as persistent, physics-based objects, this would radically change the ways in which games are experienced, and how genre is perceived.

Would Far Cry be a first-person shooter if you could drop your gun, dig out two pairs of fence-posts, pitch them on opposite sides and kick a chicken between them? What would happen if you punched someone in the stands in FIFA? Would it even be a football game anymore? These questions become even more relevant when you factor in the rise of VR. The main reason VR experiences feel “real,” as opposed to something akin to watching Imax is presence. When your grippy Oculus Touch hands appear in front of you and you actually pick things up, observe them, toss them at the wall, your environment becomes a lot more than a decked-out stage because the objects that comprise it at least appear to have an objective existence: That over there is a pot, not a representation of a pot, because you can get close to it, turn it over in hour hands, stuff some other object inside it (if collision detection allows).

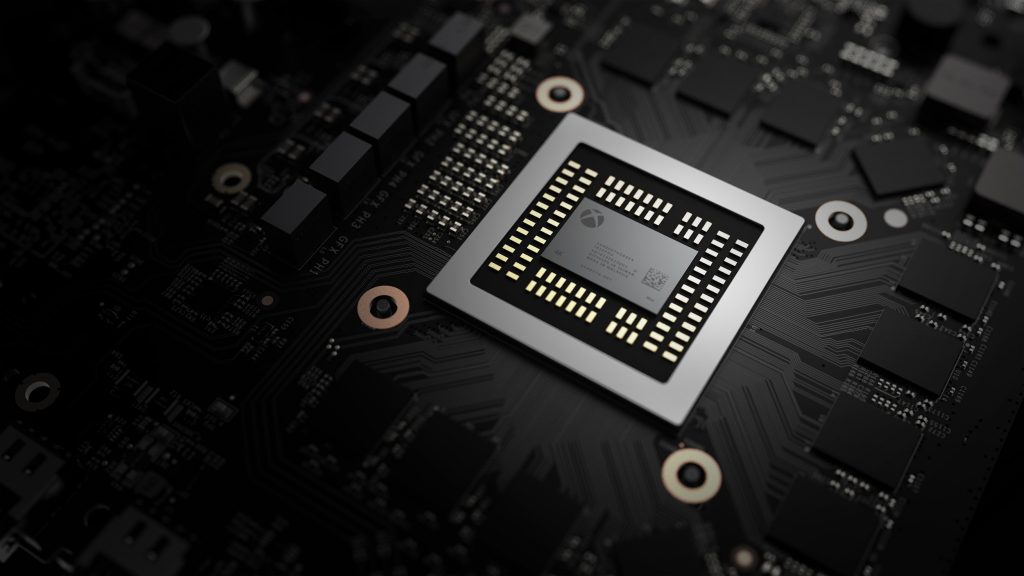

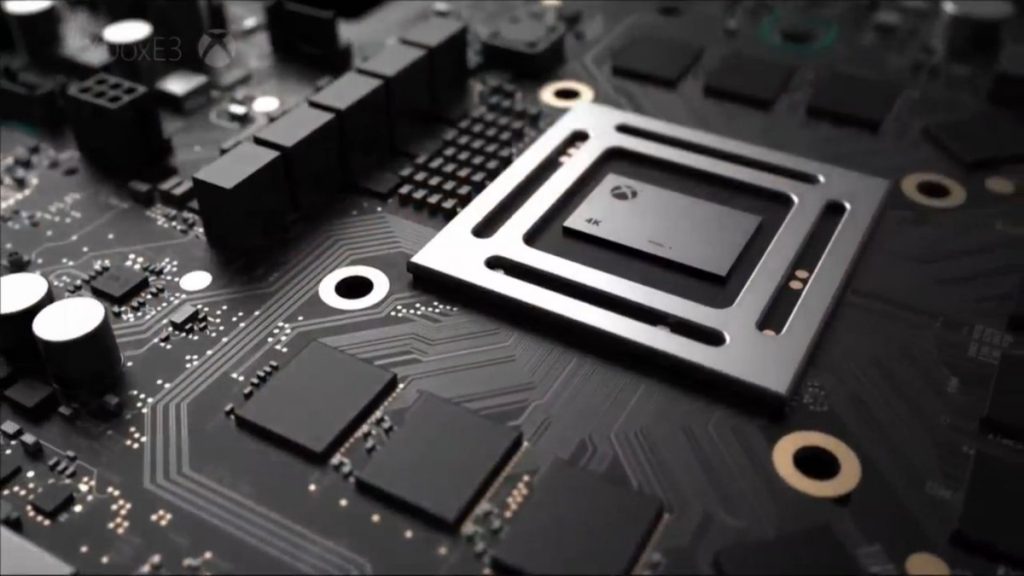

"The current mid-cycle refresh consoles give us a good idea of what next-gen 4K gaming may look like, frame-to-frame."

It’s the perception that the assets in an environment exist objectively, independent of your actions that leads to a feeling of presence. In contrast, the way we engage with games like The Witcher 3 has more in common with listening to a story or watching a stage-play: the pot over there is a representation of a pot. Move too close to it and Geralt might clip right through. The representational pot requires suspension of belief in a way that the “real” VR pot does not. As Frictional Studios’ work goes to show, the objective existence of objects isn’t limited to VR: a part of what makes The Vanishing of Ethan Carter narrative so compelling is the ability to engage with the environment objectively: picking up objects, flipping through pages, reading through smudged ink, as opposed to going through a “quest-log” or chasing points on a map. With computing constrainst lifted, these kind of experiences no longer need to be restricted to the confines of a walking simulator: think open worlds with the kind of moment-to-moment presence experienced in the likes of What Remains of Edith Finch and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. This is what’s the ninth gen is likely to look like—barring unsustainably high development costs. Well, imagine a lootbox that you can pry open with your—never mind.

The current mid-cycle refresh consoles give us a good idea of what next-gen 4K gaming may look like, frame-to-frame. However, if the PS5 and Xbox…Whatever successfully eliminate CPU constraints (likely thanks to a Ryzen-based platform), the experience of playing games will likely experience a paradigmatic shift. And well it should. It’s almost 2020, for crying out loud. It’s supposed to be the future!