By Jesse Nivens, Developer at Gristmill Studios.

Hello everyone! This is Jesse Nivens, I do art and interface at Gristmill Studios, the developers of XenoMiner. To get things started, I’ll introduce you to the group and how we work. Gristmill began with three software developers working together at a large business in Madison, Wisconsin: Rod Runnheim, Shaun Nivens and Doug Graham. They bonded over gaming and a shared interest in trying to make them. After that, other co-workers and friends saw something cool happening and wanted to get involved, so the group grew. Shaun (my brother) went on to work for a larger gaming company, but not before bringing me in as an artist.

There are now 6 developers and 3 artists on the team. We have a system for getting games and projects done that we started two years ago: We set aside one night a week (Tuesdays) to all get together and work. But it’s more than just work, it’s hanging out (at developer Doug’s house), eating pizza and bullshitting. A consistent work time not only keeps the project moving forward, but it removes lingering stress from your other nights. What I mean is this: You can spend all week thinking “I need to go into the code and fix that bug,” and then finally actually do it. So the task becomes a weight. It’s better to just know that whatever it is, you’ll do it Tuesday. Of course, it’s not always that easy: There has been a big response to XenoMiner and we’ve been caught in a whirlwind, often having two formal developer get-togethers per week and individual tasks spread throughout the evenings.

XenoMiner is an Xbox Live Indie game that began life early in 2012. Before that, we released Devilsong on XBLIG in 2011 along with doing most of the work on a game called Etch. It’s a tower defense game for iOS, but the iOS marketplace is so crowded that we decided to hold off on releasing it until we built a bit more recognition for the studio.

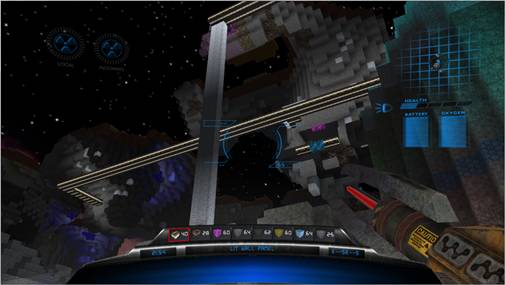

XenoMiner is a spin off the block-building voxel genre. Since we created it in a scifi setting it really opened up a lot of new options. The first of those, and one of the major reasons we made this game in the first place, is the programmable bot. Everyone who has played a sandbox game has at some point wished they could send out a robot to do some of the grunt work for them.

The robot is a good place to start talking about some of the challenges we’ve had with the game: there have been ups and downs as far as how the community has taken the robot. First I should say that people universally are thrilled to hear that there is a voxel game with an integrated scripting language. We made it hard to use: the language is composed entirely out of alien characters. It took players around 3 days to crack the code (we knew the hive mind could do it, actually it was surprising it was that quick!). Of course, people immediately started posting tutorials on our forum or youtube, so the information is out there.

That’s not enough for everyone though: As one of our fans (angrily) wrote in, only hard-core players are going to jump onto the web and google around enough to figure out how to make the thing work. It’s the classic development problem of “how hard is too hard?” Our thinking so far has been that the bot is a powerful tool that can be used to do just about anything, so if someone wants that power they should put in some effort to get it. We don’t view it as some type of puzzle to figure out in order to advance the plot: if the player doesn’t want to write a working script, they don’t have to. In the meantime, we started a discussion on our forum to get our player’s opinions. There are some good ideas posted on the topic that we’ve been thinking about using.

That’s all the time I have for now, if you have questions, comments, or just want to talk, comment here or drop me an email. Our website is gristmillstudios.com. We’re also on Facebook and Twitter.